Shimooka Renjō and the Japanese Carte-de-visite: Thoughts on 'A carte album attributed to Shimooka Renjo'

Japan by the Dozen

Please go to the Japanese photographer who resides in a street near Benten [Shrine]; ask to see everything that he has taken since the spring of 1864, and make a selection (…) of what you consider his best work. I already have from him two seated women, one with a pipe in her hand, a naked woman on a monument, and several yakunin. Get whatever he has taken recently of women as well as craftsmen, but especially women of various kinds; as for yakunin and the people at the custom house, I already have enough of those. I no longer have any need for views of Yokohama. (…)1

‘Je vous prie d’aller chez le photographe japonais qui demeure dans une rue près de Benten; de lui demander de voir tout ce qu’il a fait depuis le printemps de 1864, et de choisir (…) ce que vous trouverez de mieux. J’ai déjà de lui deux femmes assises l’une ayant la pipe à la main, une femme nue appuyée sur une monument, et quelques yacounines. Prenez tout ce qu’il aura de nouveaux en fait de types de femmes; et aussi d’artisans; surtout des types de femmes; quant aux yacounines et types de la douane, j’en ai assez. Je n’ai pas besoin non plus de vues de Yokohama.’ Aimé Humbert to François Perregaux, 7 June 1865, Archives de l’État de Neuchâtel, fonds Humbert 8, folios 467-69, quoted in Grégoire Mayor and Akiyoshi Tani (ed.) Japan in Early Photographs. The Aimé Humbert Collection at the Museum of Ethnography, Neuchâtel, Stuttgart: MEN Arnoldsche Art Publishers 2018 228. The translation is mine.

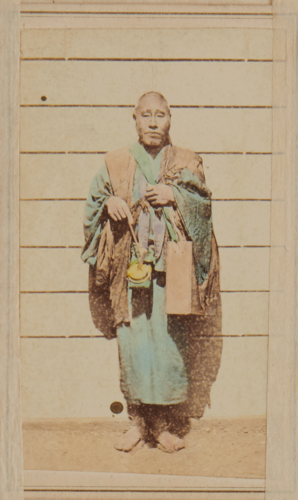

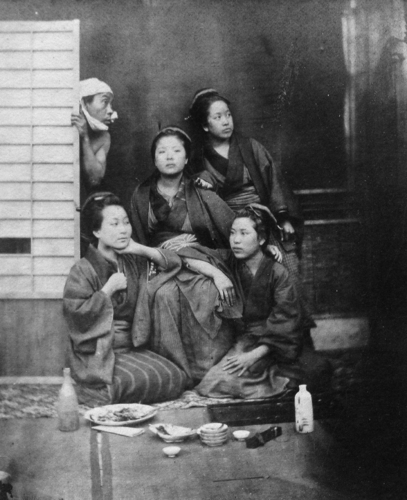

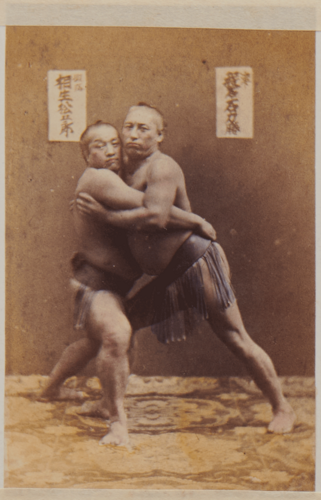

With these simple instructions written in June 1865, the former Swiss envoy to Japan, Aimé Humbert, commissioned a friend living in Yokohama to visit the studio of Shimooka Renjō and acquire some more photographs for his collection. In his list of preferences, Humbert provides a glimpse of a portfolio that we would recognise immediately when leafing through this album, since, with the exception of Renjō’s elusive female nudes, all the subject matter described in Humbert’s letter, in particular, women, yakunin, or samurai officials, and artisans, is well represented here.2 The scarcity of Renjō’s portfolio of nudes is discussed in Ishiguro Keishō, ‘Shimooka Renjō’s Nude Photography’, in Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography (ed.), Shimooka Renjō – Nippon shashin no kaitakusha/ Shimooka Renjō: A Pioneer of Japanese Photography, Tokyo: Kokusho Kankōkai 2014 2014 138-39.An examination of the actual examples of Renjō’s work in the Humbert Collection, as well as the engravings based on his photographs that went on to appear in Humbert’s published works on Japan, reveals not only more overlapping subject matter - samurai in armour, sumo wrestlers, tattooed labourers or bettō, street entertainers, street vendors, family groups and artfully arranged scenes that defy classification

- but even a couple of direct matches.3 78 and 109 in this album match MEN P.1950.1.59 and MEN P.1950.1.90 in the Humbert Collection, while 100 is reproduced as an engraving entitled ‘Moulin à riz’ in his work Le Japon Illustré. Mayor and Tani 2018 55, 253; Aimé Humbert: Le Japon Illustré, Paris: Librairie de L. Hachette et Cie. 1870 vol. 1 89. By the time Humbert’s final round of purchases from the studio in Benten-dōri was completed by his proxy later in 1865, the main thematic structure of Renjō’s portfolio was already firmly in place.

Several years later, in the early years of the Meiji era, an unknown customer leafed through Renjō’s stock of cartes-de-visite with similar enthusiasm. By this time, the transaction would have taken place in one of two studios Renjō now operated in Yokohama, with an expanded portfolio to peruse and the additional option of whether or not to have the purchases coloured by hand to consider. The political and social complexion of Japan was also different, with the recent overthrow of the shogunate and the installation of a new reforming government casting a different light on much of Renjō’s subject matter. While most of his photographs still provided his foreign customers with exemplars of Japanese culture, some, viewed from the perspective of the early Meiji era, also represented a social order that was about to disappear. The motives of our visitor were probably less lofty than Humbert’s, but the appeal of Renjō’s portfolio was no less strong and inspired the ambitious purchase of 144 cartes-de-visite. This total is enough on its own to make this one of the largest groups of Renjō’s work to come down to us in its complete and original state, but what gives this collection greater significance is the form in which it has done so. Albums of any kind containing Renjō’s work are extremely rare: the handmade album in which these twelve dozen cartes-de-visite are housed is almost certainly unique.4

A rare example of a complete album of 24 cartes-de-visite by Renjō is held in the Tom Burnett Collection, New York. See www.tomburnettcollection.com/gallery/main.php?g2_itemid=365 (last accessed 17 April 2021).

Reassessing the Carte-de-visite

Before turning to the album, it is worth mentioning the format of its contents. Measuring approximately 9 x 5.5 cm (4 x 2 ½ inches) and pasted onto a slightly larger rectangle of card stock, the carte-de-visite has a modesty of scale that has earned it an ambiguous place in history. As Geoffrey Batchen as pointed out, the carte-de-visite has received short shrift from historians of photography, who have tended to ignore the use of the format by many well known nineteenth-century photographers and instead denigrate it as commercial and formulaic, even dismissing cartes-de-visite ‘as being without imagination’.5 Geoffrey Batchen, ‘Dreams of Ordinary Life: Cartes-de-visite and the Bourgeois Imagination’, in Photography: Theoretical Snapshots, ed. J.J. Long, Andrea Noble & Edward Welch, London/ New York: Routledge 2009 80. This may explain the relative lack of coverage given to the carte-de-visite by historians of Japanese photography. The work of Renjō’s contemporary - and rival - in Yokohama, the Anglo-Italian photographer Felice Beato (c.1834-1909), has long been the subject of scholarly evaluation, yet, while his better-known series of large-format Japanese ‘views’ and ‘costumes’ has been extensively examined, the carte-de-visite portfolio he issued alongside it has been all but ignored. When, as in Renjō’s case, cartes-de-visite constitute the bulk of a photographer’s known or surviving output, the attention bestowed by photographic historians can almost be grudging, with any assessment apparently best postponed until work by the same photographer emerges in more substantial formats. Even as late as 2006, one writer on early Japanese photography observed that:

As far as his [Renjō’s] photographic work is concerned, more than a hundred cartes de visite have now been positively attributed to his studio. However, his larger format work remains elusive, with just a handful of images having so far been identified. As such, it is still too early to provide a reliable critique and assessment of his work.6

Terry Bennett, Photography in Japan 1853-1912, Tokyo: Tuttle Publishing 2006 71-72.

Fortunately, the relative dearth of Renjō’s larger format work did not prevent Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography (now Tokyo Photographic Art Museum) from holding a major retrospective exhibition in 2014 to mark the centenary of his death. As the exhibition catalogue shows, of the 159 photographs featured that could be attributed to Renjō, 145 were cartes-de-visite, and other exhibitions surveying the early history of Japanese photography held at the same museum have likewise given the carte-de-visite the attention it deserves as one of the dominant photographic formats in nineteenth-century Japan.7 Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography 2014. Between 2007 and 2013, Tokyo Photographic Art Museum (formerly Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography) organised a series of four exhibitions under the umbrella title ‘The Dawn of Japanese Photography’ with each focusing on a particular region of Japan. In particular, see Tōkyōto Shashin Bijutsukan (ed.), Yoake-mae shirarezaru Nippon shashin kaitakushi II Chūbu, Kinki, Chūgoku chihō-hen, Tokyo: Tōkyōto Shashin Bijutsukan 2009, Yoake-mae shirarezaru Nippon shashin kaitakushi – Shikoku, Kyūshū, Okinawa-hen, 2011, and Yoake-mae shirarezaru Nippon shashin kaitakushi – Hokkaidō, Tōhoku-hen, 2013. See also Tōkyōto Shashin Bijutsukan (ed.), Shirarezaru Nippon shashin kaitakushi, Tokyo: Yamakawa Shuppansha 2017 and Nippon shoki shashinshi – History of Early Japanese Photography: Bakumatsu Meiji wo toru: zuroku Kantō-hen, Tokyo: Tōkyōto Shashin Bijutsukan 2020.In Western scholarship, however, the consideration of the Japanese carte-de-visite as a genre has only just begun.8 Luke Gartlan, ‘Shimizu Tōkoku and the Japanese Carte-de-visite: Circumscriptions of Yokohama Photography’, in Portraiture and Early Studio Photography in China and Japan, ed. Luke Gartlan and Roberta Wue, New York: Ashgate 2017 17-40. See also Maki Fukuoka, ‘The Fluidity of Representation: Early Photographs, Asakusa, and Kabuki’, ibid 159-173.With the publication of this important album, another 123 photographs can now be added to the published canon of Renjō’s work; an assessment of his work on the basis of his carte-de-visite portfolio no longer seems premature.9 Only 21 of the 144 photographs in this album appear in either Ishiguro Keishō (ed.), Shimooka Renjō shashinshū, Tokyo: Shinchōsha, 1999 or Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography 2014. Apart from a selection that was published in 2000, these photographs have never been published before. See Ozawa Takeshi (ed.), Shashin de miru Bakumatsu-Meiji, Tokyo: Sekai bunkasha 2000

The Album

At some point after this group was purchased, a crude album was fashioned to house the photographs and simple captions were added in Japanese to explain the content. Whether this packaging was a service provided by Renjō’s studio is unclear, but the unusual detail provided in some of the captions indicates that they were written by someone who had particular knowledge of the subject matter and may therefore have been connected with the studio.

The album has a decidedly improvised feel to it. Fourteen leaves of paper, each measuring 33.6 x 48 cm (13 ¼ x 19 inches), were separately folded vertically down the centre and then gathered to create a crude Japanese-style binding, with the folds forming the outer edges of the pages and the loose edges the spine.10 The sheets do not confirm to any regular Japanese or Western paper size, although the shorter measurement is consistent with the British Foolscap size for uncut writing paper (13 ¼ x 16 ½ inches) and it is possible that they may have been cut down from one of the larger Foolscap variants.With the top and bottom leaves serving as covers to protect the twenty-four pages inside, the gathering was finally secured with three imported brass paper fasteners inserted down the spine. The cartes-de-visite were then laid out six to each page and held in place horizontally across the top and bottom, or sometimes diagonally at the corners, by strips of Japanese paper which were carefully pasted onto the page in order to avoid touching the photographs and their card mounts. As a finishing touch, captions in Japanese were then written vertically in ink in the right-hand margins next to the photographs. Once in the hands of its owner, the album received its final embellishment in the form of annotations in English penciled on the strips of paper supporting the photographs along the lower edge.

The rough-and-ready nature of the album is mirrored in the apparently random arrangement of the photographs, with no evidence of a consistent thematic structure being followed, and subjects such as samurai, craftsmen and sumo wrestlers are scattered evenly throughout the album. Some subsequent disorganisation of the photographs is evident: in several cases,

![Shimooka Renjō, [Illegible]/ ’Paper hangers’, c.1863-70.](https://d1m232vsyej29j.cloudfront.net/i/1f/Yf784ADWe_VibXqU.png)

![Shimooka Renjō, ‘Shinshū[shi] narabini koshimoto (Samurai of the Province of Shinshū and maidservant)’, 1868. Portrait of the silk merchant and entrepreneur Yoshiike Taisuke (1824-1877) with an unidentified woman.](https://d1m232vsyej29j.cloudfront.net/i/98/VOiU0F2B_znkFYI.png)

![Shimooka Renjō, ‘Dai-shōnin no musume [illegible] (Girl of a wealthy merchant)’, c.1863-70.](https://d1m232vsyej29j.cloudfront.net/i/3c/pqibhT6y_P7CQNP.png)

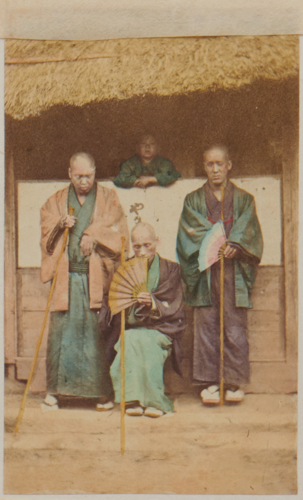

none of the captions either in Japanese or English match the subject of the photograph, as, for example, where two Buddhist priests

are misidentified as ‘An Interpreter’s sisters at the custom house’.11 The cartes-de-visite in this album are unnumbered. The numbers used in this essay are assigned by counting the carte in the top left-hand corner of the first page (‘Girl with samisin…’) as 1 and continuing the numeration from left to right and then from top to bottom. This may have resulted from cartes either being temporarily detached from the album and then returned to the wrong location or else being permanently removed and replaced with a carte of an unrelated subject acquired separately from Renjō’s studio.

The Japanese captions are simple and describe the subject of each photograph in a single line of text. Chinese characters are sometimes written in an unconventional form and occasionally the author of the captions substitutes them phonetically using the katakana syllabic script. In one instance, an error is made with the final character in the Chinese character compound jorō, meaning prostitute, but otherwise the Japanese inscriptions appear to be the work of someone who had received a reasonable level of education.

The idiomatic language in the English captions, meanwhile, indicates the hand of a native speaker, while the frequent inconsistencies with the corresponding captions in Japanese reveal an ignorance of the written language which points to the English captions having been written by someone unconnected with the creation of the photographs, almost certainly the customer for whom the album had been prepared. The author reveals the male gaze in his appreciation of one female subject,

![Shimooka Renjō, ‘Samurai no musume (Samurai's girl/s])’/ ‘Belle of Yokohama on the right’; ‘“Take care! Beware! She is fooling thee” I know her well’, c.1863-70.](https://d1m232vsyej29j.cloudfront.net/i/37/kp8HEQZ8I_u5DUue.png)

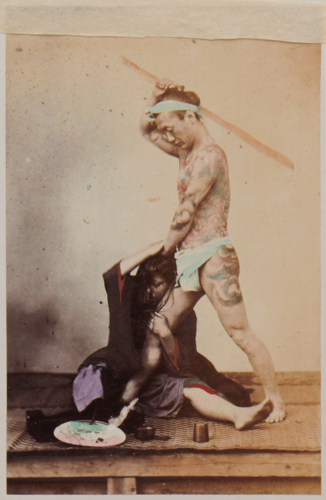

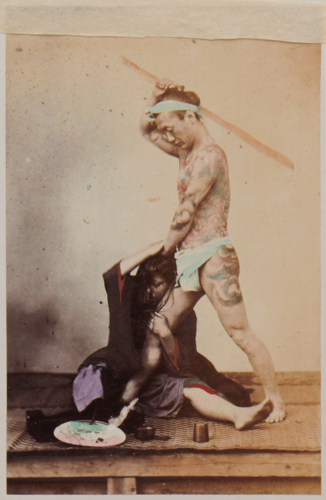

paraphrasing a poem by the American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807-1882) - ‘Take care! Beware! She is fooling thee’ - and adding, ‘I know her well’. Further embellishments of this kind appear elsewhere in the album. Renjō’s staging of a scene of domestic violence in which a tattooed bettō appears to beat his wife with a stick

prompts the observation:

I have no doubt she deserves a thrashing. The japs (sic) are generally very good tempered. They must have great provocation when they have recourse to such measures. All the bettoes are compelled to be tattooed all over the body, for what reason I do not know.

Except for an apparent interest in the gradations of samurai, and especially daimyō, rank, the owner brings little in the way of ethnographic curiosity to the subject matter of this album. Instead, the complacency of a gaze informed by the certainties of the Yokohama foreign settlement is evident, as, for example, in the annotations made to a photograph of a young women playing the tsuzumi, or hand drum:

:

As you will perceive they do not use drum sticks. The noise produced is one monotonous sound, very pleasant no doubt to a jap’s (sic) ears, but very annoying to a European.

Dating the Album

The album offers a broad sampling of Renjō’s output over the period 1863 to 1870. Two images

match prints acquired in the summer of 1863 by Aimé Humbert which are now held in the Museum of Ethnography in Neufchâtel, indicating the longevity of Renjō’s early work in his portfolio. A later benchmark in Renjō’s career is reflected in a photograph

in which a wall tiled in the namako-kabe style is used as a background. This architectural style was distinctive to Shimoda and suggests that the photograph was taken during Renjō’s sojourn in his hometown between 1865 and 1867.

The troubled political situation in Japan leading to the Boshin War of 1868-69, described in one English-language caption as ‘the late insurrection’, overshadows much of the portfolio. Samurai of all ranks from domain lords (daimyō) to shogunal retainers (hatamoto) are shown in fighting dress and described in the accompanying Japanese captions as ‘departing for battle’ (shutsujin)

or ‘at the front’ (jinchū),

while one caption in English accompanying a portrait of a ‘female warrior’

speculates that ‘many of these might have been seen fighting on both sides’. The sitter in one portrait

is captioned ‘“Enomoto” the insurgent’, misidentifying him as Enomoto Takeaki (1836-1908), who commanded the final vestiges of resistance to the new order until he was forced to surrender at Hakodate in June 1869. This indicates that the last stand of the shogun’s army was still a recent event when this album was compiled, and, to judge from the similarly baseless identifications of the female subjects of two other portraits as ‘Enomoto’s Mistress’

and ‘Another of Enomoto’s Mistresses’,

its leader was something of an object of fascination for the owner.

The transition into peacetime and the early Meiji era is firmly marked by two unusual examples of instantaneous street photography

taken during the festival that followed the installation of the guardian deity of Yokohama at the newly created Shinto shrine of Iseyama Kōtai Jingū on 14 May 1870. The senza matsuri was the first major festival to take place in the port since it opened in 1859, and the caption in English, ‘the late festival called the O Matsuri’, which accompanies one of these photographs suggests that it was still a recent event when this album was acquired.

The portfolio therefore seems suspended in the summer of 1870, before the daimyō surrendered their domains to the new government in the following year and the rapid erosion of the privileges of the samurai class ensued.

Merchants of Images

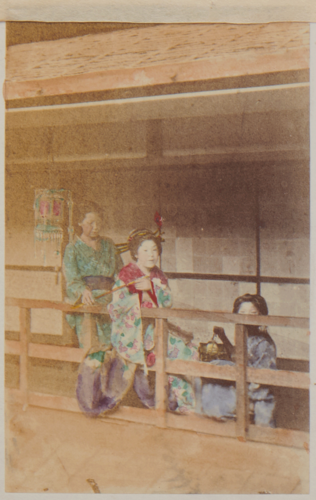

Humbert’s patronage is a particularly good example of how Renjō’s photographs served his customers as exemplars of Japanese culture and society. After Humbert’s return to Switzerland in June 1864, his acquisitions from Renjō’s studio formed part of an extensive visual resource that Humbert drew upon as he prepared his travel diary for publication, firstly in installments between 1866 and 1869 in the popular Parisian journal Le Tour du Monde and then in 1870 as the two-volume work Le Japon Illustré.12 See Grégoire Mayor, ‘“The most sophisticated processes in Western art”. The Role of Photography in Aimé Humbert’s Mission’, in Mayor and Tani 2018 15-28.The artists and engravers tasked with illustrating Humbert’s writings made extensive use of Humbert’s photographs, copying and adapting them for reproduction as woodcut engravings. In doing so, images were sometimes removed from their context to connect with Humbert’s text; in one instance, a group apparently attending a moon-viewing party

in a photograph by Renjō was uprooted from its studio location and combined with other photographs in Humbert’s collection to create an imagined scene at the Dutch consulate in Yokohama.13 Engraving entitled ‘La loge des portiers de le résidence hollandaise’, in Aimé Humbert: Le Japon Illustré, Paris: Librairie de L. Hachette et Cie. 1870 vol. 1 57.As recent scholarship has confirmed, Humbert’s photographic purchases in Japan were by no means restricted to Renjō’s studio, and a significant part of his collection was acquired from Felice Beato, who had only very recently established himself in Yokohama.

Beato’s work can be identified in the same engraving. The fact that Beato and Renjō both contributed to Humbert’s picture library invites a comparison of their work, for like Renjō, Beato had by the mid- to late 1860s established a portfolio that included ‘native portraits in cartes-de-visite, illustrative of the different dresses, customs and habits of the people’.14 Journal of the Bengal Photographic Society 1 (New Series) (March 1867) 25. Quoted in Luke Gartlan, ‘Types or Costumes? Reframing Early Yokohama Photography’, Visual Resources 22:3 (September 2006) 244.

![Alphonse de Neuville, after Shimooka Renjō and Felice Beato, ‘La loge des portiers de la résidence hollandaise [The porter’s lodge at the Dutch residence]’, engraving from Aimé Humbert, Le Japon Illustré, 1870, vol. 1, 57.](https://d1m232vsyej29j.cloudfront.net/i/d6/2XY4bEV2_kdm48I.jpeg)

If we take an album held in the Library of Congress as a benchmark of Beato’s carte-de-visite work in the late 1860s, certain similarities emerge, the most arresting being the use of hand-colouring.15 The album contains 200 cartes-de-visite, 150 of which are of Japanese subjects taken by Beato while the remaining 50, which depict Chinese subjects, are attributed to the British photographer John Thomson (1837-1921). See https://www.loc.gov/search/?fa=partof:lot+4339 (last accessed 23 April 2021).Beato employed the same Japanese colourists for both his large format work and his cartes-de-visite, even producing a scene in the latter format showing them at work on cartes-de-visite. The arrangements in Renjō’s studio are less clear: an album containing 24 carte-de-visites in a private collection bears an ambiguous inscription on its front page:

Given to me at Yokohama on the 24th May 1867, the day before I left Japan, by our Chinese Compradore, Wun Ping San. The Photographs are taken by the Japanese Photographer Ren Jio Sama and colored by native artists.16

This album from the Tom Burnett Collection in New York is discussed in Mitsui Keishi, ‘A Pioneer of Japanese Photography: Shimooka Renjō’s Place in History’, in Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography 2014 181-84.

It is unclear at what stage these ‘native artists’ entered the process between Renjō creating the cartes as part of his stock and their subsequent purchase and packaging into an imported carte-de-visite album for presentation as a gift to the unidentified recipient. Were they already coloured when they went on sale or did arrangements have to be made to have them coloured afterwards, either with Renjō’s assistance or separately? Given Renjō’s artistic background, it is possible that colouring was a service he was willing to offer his customers for an additional fee.

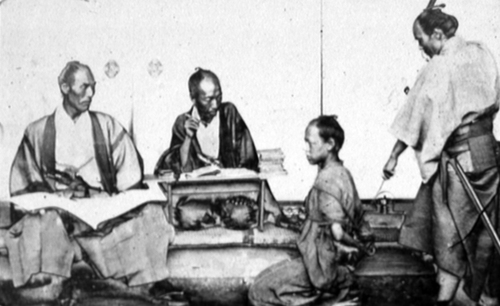

As Renjō and Beato developed their portfolios after opening their studios in 1862 and 1863 respectively it would be natural for some degree of overlap to occur, especially as each sought to attract foreign customers from the same client base in Yokohama. Nevertheless, beyond the more generic categories such as young women, yakunin, street traders, tattooed bettō, and sumo wrestlers, there are some similarities in subject matter that do not appear coincidental. The scene of a bound criminal being examined by a magistrate

![Shimooka Renjō, ‘Yakunin nusubito wo shiraberu tokoro [Official examining thief]’/ ‘Examination of a culprit’, albumen print, c.1863-65.](https://d1m232vsyej29j.cloudfront.net/i/34/sJY9KQE1_8bhN6P.png)

is represented in both photographers’ portfolios,

and suggests some degree of awareness on the part of at least one photographer of what his competitor was producing. Some of the cartes in this album seem to emulate Beato’s almost ethnographic treatment, which seems to favour a full length arrangement for his subjects with a neutral background and a simple Japanese floormat providing minimal distraction for the viewer.

However, even when striving for this kind of minimalism, Renjō reveals his own preferences. In two photographs of sumo wrestlers and an umpire,

a paper label is pasted behind each subject bearing his name and sometimes his rank. This conscious imitation of the daisen, or title cartouche, used in nishiki-e portraiture to identify the sitter dates from Renjō’s earliest known work and it is worth remembering that the sale of Japanese woodblock prints was a significant side business of his Zengakudō studio.17 A group portrait of five yakunin by Renjō acquired by Humbert during 1863-65 (MEN P.1950.1.114) employs the same device to identify the sitters. Mayor and Tani 2018 249. Curiously, two photographs by Renjō of similar vintage in the same collection showing sumo wrestlers (MEN P.1950.1.93 and MEN P.1950.1.94) do not feature any such identifying labels. Ibid 236-37.

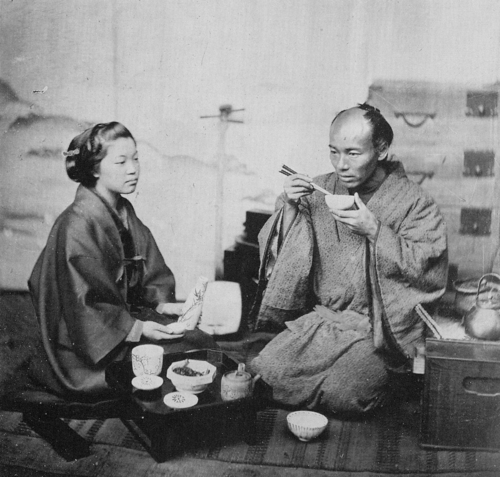

This minimal approach, however, does not appear to have been consistently applied by Renjō to his studio work. Clutter is the prevailing impression one is left with after leafing through this album, with his unused studio furnishings, such as backboards and plinths, and other paraphernalia such as neck-braces, frequently appearing in the camera’s field of vision. Painted backdrops are combined with traditional screens, Western-style woven carpets jostle with Japanese straw mats, and curtains appear alongside traditional sliding doors.

The differences between Beato and Renjō are particularly apparent when we compare their respective handling not just of similar subject matter but of the same sitters. As this album reveals, Renjō recruited two models who also featured in Beato’s work. The question of which photographer had prior authorship of their likenesses need not concern us here, but, given the celebrity status both sitters had in Yokohama in the mid- to late 1860s, it is hard to imagine either Renjō or Beato being unaware of the fact that the itinerant dentist Ishii Shinnosuke (dates unknown) and the local beauty known only to posterity as the ‘Belle of Yokohama’ had already been photographed by his rival and that both subjects enjoyed a celebrity which made them highly marketable.

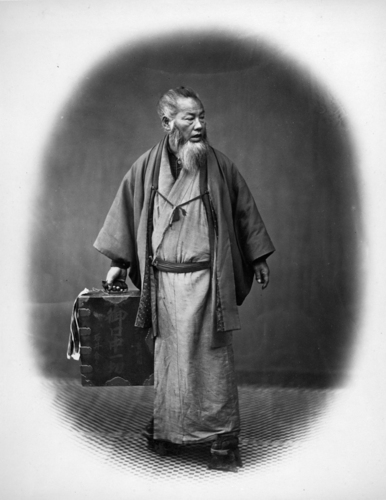

The most recognizable of the two is the individual referred to in Japanese as ‘haisha’ (dentist) and described by the owner of the album as ‘The Dentist – a well known character here’.

![Shimooka Renjō, ‘Haisha [Dentist]’/ ‘The Dentist - a well known character here’, albumen print, c.1867](https://d1m232vsyej29j.cloudfront.net/i/6c/XccRBdH8P_fXnd5A.png)

The same man, this time unaccompanied by his servant and without a sword, features in the portfolio of larger format ‘costume’ studies that Beato issued in 1868 under the title ‘Travelling Dentist’,

and is thanks to the higher definition in Beato’s portrait that the sitter can be identified from the inscription on his lacquer travelling case. The identification of the ‘Belle’ was made more incidentally when the owner added the inscription ‘the Belle of Yokohama on the right’ to a portrait of two young women identified in Japanese as ‘samurai no musume’, suggesting that they were either the daughters or the mistresses of samurai.

![Shimoka Renjō, 'Samurai no musume [A samurai’s girls]’/ ‘“Take care! Beware! She is fooling thee” - I know here well’, albumen print, c. 1866-67.](https://d1m232vsyej29j.cloudfront.net/i/37/kp8HEQZ8I_u5DUue.png)

This is a direct reference to the moniker under which the same sitter appears in Beato’s portfolio of ‘costumes’. The unknown ‘Belle’

is a frequent model in Beato’s work, referred to at least three times in the printed captions accompanying his cartes-de-visite and making uncredited appearances elsewhere in both his larger and smaller format work. Her story remains unclear, though Beato’s work reveals the unusual detail of a ring on her ring finger. This item of bodily decoration was practically unknown in Japan at this time, and in this case may have been a token received from a foreign admirer. The leering comment ‘I know her well’ made in by the owner in his original caption to her photograph may have been joking in intent, but says much about the basis of her fame in the male-dominated foreign community of Yokohama.18 See Eleanor M. Hight, ‘The Many Lives of Beato’s “Beauties”’, in Colonialist Photography: Imag(in)ing Race and Place, ed. Eleanor M. Hight and Gary D. Sampson, London: Routledge 2002 126-58

While Beato’s treatment of the ‘Dentist’ and the ‘Belle’ reveals the consistency of his studio style, with both placed against a neutral background and foregrounded on a simple floormat, their corresponding portraits in this album reveal little consistency on Renjō’s part except for his trademark clutter. While the ‘Belle’ and her companion perch on a low stage concealed beneath three differently designed carpets, the dentist and his attendant stand on bare wooden floorboards in front of the same stage, this time exposed, with a bundle of brushwood placed behind them. The only shared feature seems to be the folding screen in the background.

The most striking illustration of the difference between the two photographers, however, is provided by the ‘Belle of Yokohama’. Although she shares the space in Renjō’s photograph with another young woman, she secures the viewer’s attention by directing her gaze straight at the camera lens. This is in marked contrast to her more feminised treatment in Beato’s work, where she is invariably posed in a three-quarter arrangement with her gaze directed demurely away from the camera. The returned gaze of his subjects characterises much of Renjō’s early work,

with single subjects invariably looking at the camera, while in the case of groups, one of their number usually does so. Renjō’s subjects only seem to direct their gazes away from the viewer when reenacting scenes of daily life.

The averted gaze takes on a new meaning in Renjō’s portfolio where the subject is posed with their back turned to the viewer, leaving little or nothing of their face visible, an arrangement Beato only seemed to employ when photographing tattooed labourers, presumably in order to show their body art to full effect. In this album, a variety of subjects turn their back to the viewer: a samurai in full armour,

a low-ranking prostitute,

a young lady receiving a letter

and audience members listening to a samisen performer.

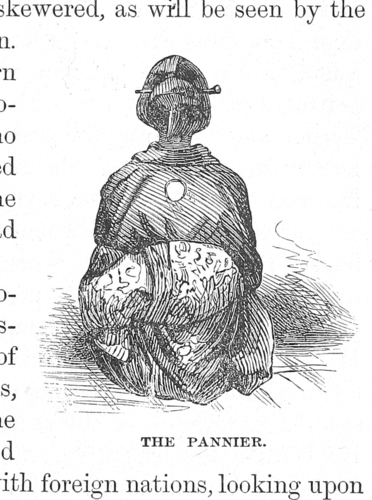

This motif was sufficiently arresting to inspire the American traveller and writer Charles Carleton Coffin (1823-1896) in July 1868 to make a purchase at Renjo’s studio during a visit to the curio shops of Yokohama:

Passing into an adjoining shop, we find very good photographs, taken by a native artist. The wife of the photographer waits upon us, and is pleased when we purchase a picture of herself wearing a pannier [Coffin is referring here to the knot securing the sitter’s sash], with her back hair neatly combed and skewered, as will be seen by the accompanying illustration.19

Charles Carleton Coffin: Our New Way Round the World, Boston: James R. Osgood & Co. 1869 451. The majority of the engravings illustrating the Japan leg of Coffin’s world tour were taken from photographs he purchased at the studio of Felice Beato.

Coffin’s account offers the additional detail that Renjō seems to have recruited members of his family as models, and we can only speculate as to whether his wife Mitsu and other members of the Shimooka family - not to mention Renjō himself and his apprentices – appear in some of the photographs in this album.

A further difference between Renjō and Beato is the frequent appearance of imported Western objects in the former’s portfolio. Western-style furniture and furnishings appear frequently alongside the familiar props of a photographic studio such as a Doric column on a plinth

and even a pair of unused neck clamps.

![Shimooka Renjō, ‘Satsuma shi[?] (Satsuma clansmen)’/ ‘A group of officers’, c.1867-69.](https://d1m232vsyej29j.cloudfront.net/i/d8/KzWCJqjJI_k1MiVe.png)

An imported octagonal mantle clock appears in two photographs of women,

testifying not only to the physical presence of foreign timepieces in daily life but also to the acceptance in Yokohama of the Western standard for measuring time. Imported objects are presented in other ways that connect them to the subject. A yakunin interpreter wearing two swords is photographed holding a Western umbrella;

a young woman identified in Japanese as a jorō from Mishima and more coyly in English as a ‘Teahouse Attendant’

strikes a confident pose with a Western chair. In Beato’s work, imported furniture of this kind is invariably secondary to the subject, who is - quite literally - a sitter; in this portrait, it is central to the composition, with the subject demonstrating her agency by standing next to the chair rather than sitting on it, with her hand placed on the backrest implying if not ownership then at least familiarity.

Another distinctive element in Renjō’s photography is the way in which scenes are staged in front of the camera. As we have seen earlier in the case of a studio reenactment of a criminal being brought before a magistrate, this use of performance was something Beato also experimented with, but apart from a couple of outdoor action shots he created with local samurai, it remained a largely understated element in his portfolio of ‘costumes’.20 Mayor and Tani 2018 209.Renjō, on the other hand, seemed to explore its possibilities further. Not only did he produce another mise-en-scène showing a criminal under investigation, but, as this album shows, he experimented with different forms of staging both in his studio and outdoors.21 This is part of the collection of negatives assembled in Japan by Wilhelm Burger in 1869-70 and held in the Austrian National Library. Tōkyō Daigaku Shiryōhensanjo koshashin kenkyū purojekuto (ed.), Kōseisai gazō de yomigaeru: 150-nenmae no Bakumatsu-Meiji shoki Nihon - Burugā & Mōzā no garasu genban shashin korekushon, Tokyo: Yōsensha, 2018 (fig. 114) 150.In the former setting, tenderness is contrasted with violence as one scene shows a young woman reading a love letter, apparently oblivious to the go-between standing behind her,

while a few pages earlier, a woman is held down by her husband as he beats her with a stick;

outside his studio, Renjō evokes a mood of foreboding in a street scene in which a pickpocket eyes a potential victim from behind a stone lantern.

A different kind of performance is evident in four photographs showing women dressed in male costume. One,

accompanied by the English caption ‘a young girl dressed as a Yakonin’, shows a young woman kneeling on a tiger-skin rug with a sword held in her left hand. The right-hand lapel of her kimono has been loosened to offer a glimpse of her upper breast and part of the undergarment beneath, giving the portrait a sexual charge. In the three other examples, the subjects all wear the hanten coat, haragake apron and tight momohiki legwear associated with artisans and labourers. In two portraits, the cross-dressers are identified by the parts they are playing: in one,

a woman wearing a headcloth and holding a lantern is described in both the English and Japanese captions as a tobi or fireman, while in the other,

the subject, identified in Japanese as a sakan or plasterer, displays a tobacco pouch and pipe as if to affirm her assumed gender and wears her headcloth knotted under the nose in the hanakake style traditionally associated with a disguise worn by thieves. Only in one instance,

do the authors of both sets of captions reveal that they are aware of the imposture, describing the subjects as ‘carpenter’s girls dressed in men’s clothes’ in English and ‘carpenter’s girls’ in Japanese.22 The original location of this photograph in the album was almost certainly where #42 is now.With their feminine hairstyles partly concealed by head cloths, the three subjects pose nonchalantly in their outfits while deploying a flask of sake, sake cups, a tobacco pouch and pipes: the two seated women pose confidently, one with her legs crossed.

This theme of cross-dressing, and especially of women dressing in men’s working clothes, appears elsewhere in Renjō’s work and is notably absent from Beato’s portfolio.23 See Ishiguro 1999 103, 137 and Tōkyō Daigaku Shiryōhensanjo koshashin kenkyū purojekuto 2018 (fig. 108) 149.What inspired Renjō to explore this playfulness with gender is unclear. One source might have been the world of the licensed quarters that features so prominently in this album. Cross-dressing was the basis of a popular annual spectacle in the Yoshiwara pleasure district of Edo during the Niwaka festival, in which courtesans dressed in male costume and performed simple theatrical pieces. Outside the licensed quarter, similar spectacles took place at major festivals in Edo and elsewhere, with local geisha and courtesans appearing in male costume in so-called ‘supplementary festivals’, or tsuke-matsuri. After the inauguration of Iseyama Kōtai Shrine in 1870, the same phenomenon could be observed in Yokohama.24 An early illustrated report of one such festival in Yokohama, including a sketch of ‘Girls dressed as Boys’, was sent to the Illustrated London News by its resident artist, Charles Wirgman (1832-1891), although it is unclear when he witnessed it. ‘New Year’s Festival Procession at Yokohama, Japan’, Illustrated London News (13 January 1872) 41-42. These public outings by courtesans in male dress were a popular subject for producers of woodblock prints, and, given the fact that nishiki-e were a significant part of Renjō’s stock-in-trade, this may have provided him with further inspiration to explore the theme of cross-dressing in his photographic portfolio.25 See Watanabe Akira, Edo no josō to dansō - Cross-dressers in Ukiyo-e, Tokyo: Seigensha 2018 9-54.This is an aspect of the portrayal of Japanese women in nineteenth-century photography that still awaits further scholarly investigation.26 Several interesting contemporary examples of cross-dressing appear in the collection of photographs assembled by Charles A. Longfellow, the eldest son of the American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, during his extended visit to Japan from June 1871 to March 1873. While in Tokyo, Longfellow commissioned a local photographer to photograph himself and prostitutes from the Yūmeirō brothel in Japanese carpenters’ outfits. See Christine M.E. Guth, Longfellow’s Tattoos: Tourism, Collecting and Japan, Seattle: University of Washington Press 2004 86.

Sex and Death

One photograph in this album

represents two particular strengths of Renjō’s carte-de-visite portfolio. Captioned ‘Yakonins with their mistresses’ in English and more bluntly in Japanese as ‘yakunin buying prostitutes (yakunin no jorō-kai)’, it shows a group of three samurai officials and their servant dallying with three young women while an older woman, who appears to be a procuress, occupies the centre of the composition. The two occasionally intersecting worlds of the pleasure quarters and the samurai class are as much a feature of Beato’s portfolio as Renjō’s, but the coverage provided by the latter has the depth one would expect from a native photographer whose reputation and connections would have enabled him to recruit subjects not easily available to his foreign rival.

Renjō seems to follow the tradition of the ukiyo-e genre by depicting the inhabitants of the pleasure quarters and its inhabitants, or at least displays more than a passing familiarity with this twilight world. The generic term jorō appears no fewer than nine times in this album alongside more specific terms and the hierachy of licensed sex work is well represented, from high-ranking oiran of the licensed pleasure quarters to lowly prostitutes operating from tenements or nagaya. The geographical range is also broad, covering not only the Yoshiwara quarter of Yokohama

and its exclusive Gankirō brothel

but also of the Shinagawa quarter in Edo/Tokyo,

the post station of Mishima

on the Tōkaidō highway and, even further afield, Osaka.

Two captions refer to the transaction of jōro-kai (buying prostitutes)

while the subject of another photograph

is identified as a woman working at a hikite-jaya, a tea house that arranged introductions between prostitutes and would-be customers.27 One photograph bears the mysterious character combination ‘bai’ and ‘jo’ (買女), a word that does not exist in Japanese, unless one reverses it to create the reading ‘onna-kai’ (女買い), which would translate as ‘buying women’. Alternatively, the first character ‘bai’ meaning ‘to buy’ may have been written in error for its homophone meaning ‘to sell’, which would create the term baita (売女), meaning prostitute. The portfolio even explores the more precarious margins of this peripheral world: the caption to one carte

refers to rashamen, a derogatory term used to describe the mistresses of foreign men or simply prostitutes who catered to Westerners, though it is unclear whether it is applied to the women in the photograph or the doll which one of them is holding, while other outsiders are represented in a portrait of two young women

identified as ‘moguri no musume’, or ‘unlicensed girls’.

For all his professed familiarity with the ‘Belle of Yokohama’, the owner of the album displayed a marked reticence when applying his captions to photographs of subjects connected with the pleasure quarters. In two cases he uses French - ‘une belle du demi-monde’ - next to photographs where the subject is identified in Japanese as either ‘Number One Prostitute in Yoshiwara (Yoshiwara ichiban jōro)’

or ‘geisha’,

while women described bluntly in Japanese as ‘jorō’ are introduced as ordinary women, ‘beauties’, or not at all. When the nature of the subject’s employment is unavoidable, the owner lapses into vernacular - ‘Free and easy’

- or where prostitutes are paired with male customers,

they are described as their ‘mistresses’. The term ‘mistress’ is applied five times, even to women who are not specifically described as such in the original Japanese caption, and when the specific Japanese term mekake is used, indicating the concubine of a yakunin,

she is described as his wife.

The frequency with which the Japanese term for prostitute appears in this album is separately matched by the terms yakunin and hatamoto, respectively indicating an official and a shogunal retainer, which are in turn closely followed by the word daimyō, indicating the lord of a domain, which appears eight times. Similar subjects appear in Beato’s portfolio, but portray an outsider’s view of a world that was encountered mainly on an official basis as the photographer made the most of his connections with the foreign diplomatic missions in Yokohama and Edo. Renjō may have had less privileged access to members of the samurai class than Beato but, as a former ashigaru footsoldier with an hereditary entitlement to wear the distinctive swords of the warrior caste, his access was certainly less restricted. Nor should the advantages of shared language and nationality be ignored, and one can imagine that, regardless of rank, the samurai who sat for Renjō felt more comfortable entrusting their likeness to a Japanese photographer than a foreign one.

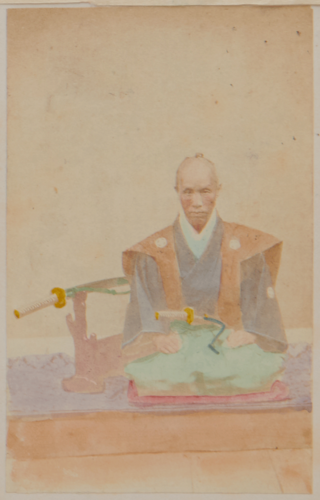

As we have seen, the political instability prevalent in Japan in the 1860s which culminated in 1868 with the outbreak of civil war provided a boost to Renjō’s business as many samurai responded to the possibility of violent death by having their portraits taken as an act of self-memorialisation. While the majority of the samurai portraits in this album give no indication of which side the sitters did fight on in the Boshin War, it is evident that supporters of both the Tokugawa shogun and the Meiji emperor are represented. In one photograph,

![Shimooka Renjō, ‘Satsuma shi\[?\] (Satsuma clansmen)’/ ‘A group of officers’, c.1867-69.](https://d1m232vsyej29j.cloudfront.net/i/d8/KzWCJqjJI_k1MiVe.png)

a group of samurai poses confidently in Renjō’s studio in a mixture of Western and Japanese military dress, the caption in Japanese identifying them as retainers of the western domain of Satsuma, one of the main supporters of the imperial cause. Having fought their way east after their initial victories over the shogun’s forces outside Kyoto and Osaka, these samurai presumably took advantage of the interval between the largely bloodless capitulation of Edo and the resumption of fighting in the north to visit Yokohama and commission this portrait to commemorate their successful participation thus far in the campaign to restore imperial rule.

The other side is represented in a photograph

in which the Boshin War has particular resonance. While misidentified as ‘“Enomoto” the insurgent’ by the owner and described simply in Japanese as a ‘gun daishō’ or army commander, the sitter can be verified from other sources as Nakajima Saburōsuke (1821-1869), a shogunal retainer who also took part in the siege of Hakodate but, unlike Enomoto, died in battle two days before the citadel fell to imperial forces.28 The same portrait, with the sitter identified as Nakajima Saburōsuke, is contained in an album which originally belonged to the family of a shogunal retainer by the name of Takahashi and is now held in Numazu City Archives. Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography 2014 57. In this portrait, the hybridised military dress typical of both sides during the Boshin War is evident, with Nakajima wearing a Western-style tunic and cape alongside the traditional double-sword combination of a samurai. Nakajima’s expression is one of resignation, almost in anticipation of his fate, and this portrait would certainly have been commissioned before he left Edo in August 1868 to join the shogunal forces as they regrouped in the north of Japan. There is also the possibility that photographer and sitter were old acquaintances, since we know that they had both been employed at the office of the Uraga bugyō, or governor, almost twenty years earlier.

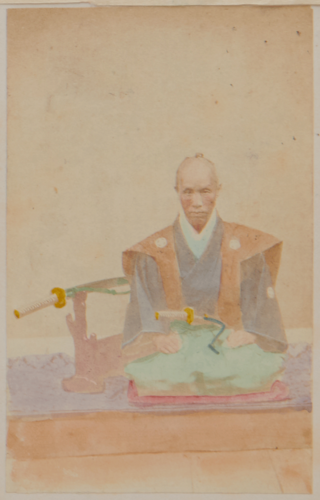

However, as one photograph

![Shimooka Renjō, ‘Shinshū[shi] narabini koshimoto (Samurai of the Province of Shinshū and maidservant)’, 1868. Portrait of the silk merchant and entrepreneur Yoshiike Taisuke (1824-1877) with an unidentified woman.](https://d1m232vsyej29j.cloudfront.net/i/98/VOiU0F2B_znkFYI.png)

shows, the act of self-memorialisation could be made for a different reason. At first sight, the portrait of this imposing individual bears the conventional trappings of samurai rank, such as a crested kimono and two swords, the largest of which is held by a woman sitting beside him who could be his wife or a maidservant. His identity, inscribed in Japanese and English on a kakemono behind him, is revealed as ‘Yoshiike Taisuke of Yoda in the province of Shinshū’, and a supplementary inscription just legible in the left-hand margin gives the date of the sitting as the spring of 1868. The sitter was no warrior, however, and neither was he setting off to war. Yoshiike Taisuke (1824-1877) was in fact a wealthy silk merchant from present-day Nagano Prefecture who had made his fortune in Yokohama and at some point acquired samurai status. Unlike many other samurai who commissioned their photographic portraits at this time, Yoshiike had more reason than most to look forward to the opportunities offered by the change of regime. In 1867, he had given his financial backing to the construction in Edo of Japan’s first Western-style hotel and work on the building would be completed before the end of 1868. Although initiated under the shogunate, this project, which coincided with the move of the nation’s capital from Kyoto to Tokyo and the anticipated opening of the city to foreigners, was in keeping with the spirit of the new Meiji era, and during its brief existence (the hotel burned down in a fire in 1872), the so-called ‘Hoteru-kan’ in Tsukiji, with its mingling of Western and Japanese architectural elements, became one of the wonders of the new capital and a popular subject for makers of woodblock prints. The hybrid nature of the building may have been consciously mirrored by Yoshiike himself when he chose to be photographed with parallel texts in English and Japanese introducing him to the viewer.

The appearance in this album of personally commissioned work such as this alongside work which we would recognise as manufactured for the foreign gaze indicates that the distinction applied by photographic historians between so-called ‘domestic’ photography intended for local Japanese consumption and ‘export’ photography intended to provide foreign residents and visitors with a picture library of Japanese cultural exemplars was a lot more blurred when this album was assembled in 1870.

Winners and Losers

The album reveals one other aspect of photographic practice at that time which reflects both the commonality and the difference between Beato and Renjō. The need to create a marketable portfolio of samurai portraits required them to supplement this section of his stock by incorporating the work of other photographers. In 1867, Beato secured the right to distribute a pair of portraits of the shogun Tokugawa Yoshinobu which had been taken earlier that year by the British naval officer and amateur photographer Frederick William Sutton (1832-1883) during an audience at Osaka Castle.29 See Sebastian Dobson, ‘Frederick William Sutton, 1832-83: Photographer of the Last Shogun’, in Sir Hugh Cortazzi (ed.), Britain and Japan: Biographical Portraits, Volume IV, London: Japan Library, 2002, 289-302.Issued as part of Beato’s stock of cartes-de-visite, they crowned a portfolio that already included senior shogunal officials, the local bugyō and a variety of samurai. Renjō was presumably aware of Beato’s coup and seems to have employed a similar strategy to augment his own work by coming to an arrangement with the Kyoto-based photographer Hori Yohei (1826-1880). Hori’s position as the foremost photographer in the imperial capital gave him unrivalled access to the shogunal administration, and three portraits

taken in his studio of high-ranking officials in full ceremonial dress appear in this album. One of the subjects can be identified as Iwata Michinori (1826-1907), the head of the Kyoto Mimawarigumi, a shogunal force responsible for public order in the city.30 Morishige Kazuo, ‘Kondō Isami no shashin ni tsuite’, in Shibuya Masayuki et al: Eisakutachi no shōzō shashin, Tokyo: Watanabe Shuppan 2010 193-255.Renjō’s connectedness to the growing community of Japanese photographers in the early Meiji era is further implied by the appearance in this album of a portrait of a samurai

![Uchida Kuichi, [Illegible] (Portrait of unidentified samurai), c.1868-70](https://d1m232vsyej29j.cloudfront.net/i/d2/t3qSRA6TI_4LVrAx.png)

taken by the up-and-coming photographer Uchida Kuichi, who had recently opened a studio in Yokohama in 1868.

The appearance in this album of a carte-de-visite

by the British photographer Charles Parker (c.1826-?) tells a different story.31 The same samurai portrait by Charles Parker appears in Bennett 2006 103.Parker had established his studio in Yokohama in the spring of 1863, a couple of months before Beato, and for a time he had enjoyed some commercial success. However, the competition presented by Beato’s studio eventually proved too much and after a couple of unsuccessful partnerships, Parker seems to have given up photography in 1866. The fate of his stock remains a mystery, though it has been suggested that he was bought out by Beato.32 Ibid 104.It is also unclear how Renjō acquired these examples of Parker’s work, but, whatever the case, this appropriation of Parker’s cartes-de-visite testifies to the ruthlessness of the market in souvenir photography in Yokohama as well as to Renjō’s ability not only to survive but to hold his own against a rival as formidable as Felice Beato.

Conclusion

What then are we to make of this album? It is far removed from the deluxe products we associate with Yokohama photography but the modesty of its binding, fashioned from writing paper rather than boards covered with cloth, leather or lacquer, and the irregularity of its captions, roughly handwritten in Japanese with occasional corrections and abbreviations rather than printed in letterpress or written in copybook script in English, make it no less significant. Its content as well, with a likely acquisition date in the latter half of 1870, provides a valuable cross-section of the portfolio of a photographer who was at the height of his ability and fame. Renjō's years of struggle in Yokohama during the previous decade, in the course of which he had gradually mastered darkroom practice and assiduously cultivated a customer base for his studio, were behind him, while his move to Tokyo and his gradual withdrawal from the photographic world was still five years away. By 1870, he was as much a Yokohama celebrity as some of the subjects of his cartes-de-visite. Weathering the competition from well-established foreign studios, Renjō had learned to cater to the tastes and expectations of Yokohama’s foreign residents and visitors while simultaneously serving a local Japanese clientele: for this reason, his portfolio defies the present-day tendency to divide nineteenth-century photographic production in Japan into convenient partitions: it is both ‘domestic’ and ‘export’; it is both authentic and staged, and, through the incorporation of the work of other Japanese photographers such as Hori Yohei, it represents both Yokohama and further afield. Recent research has identified work by Renjō in other photographic formats, but, as this album testifies, the carte-de-visite was as central to his portfolio as the large format print was to that of his rival Beato. With this in mind, we can perhaps begin to appreciate Renjō on his own terms.