Interview: Kanade HAMAMOTO “midday ghost”

An interview with young Japanese photographer Kanade Hamamoto about her book “midday ghost”, her exhibitions, influences and future ambitions.

— You have just toured Japan with your “midday ghost” exhibition. How did you approach the different cities and exhibition spaces?

Hamamoto:

During the tour through Japan, each exhibition was adjusted to fit the locations in which we exhibited. For each new place, I changed and reorganized various elements of the installation, making use of framed images, photos mounted on lightboxes or photos printed out at convenience stores.

The photos mounted on lightboxes drew much attention in particular. I’m very happy for all the feedback I’ve received.

— There are photographers who regard the photobook as the ultimate destination of their photographs. You keep showing and publishing your work in a variety of ways and settings, including exhibitions, installations and websites. Is there a difference between showing photographs in an installation and in a photobook?

Hamamoto:

I don’t see the photobook as the final stop for a photograph. I am using photography as a kind of material, with exhibitions as the goal. Ever since I started doing photography, I have felt some kind of anger towards the widespread idea that works are ‘finished’ once they’ve been published on social media. And that anger – or sense of urgency perhaps – only increased when online exhibitions became more prevalent with the start of the corona pandemic.

That’s also why I decided to hold a solo exhibition at two simultaneous locations in Tokyo this summer, and to tour the country with a photo exhibition.

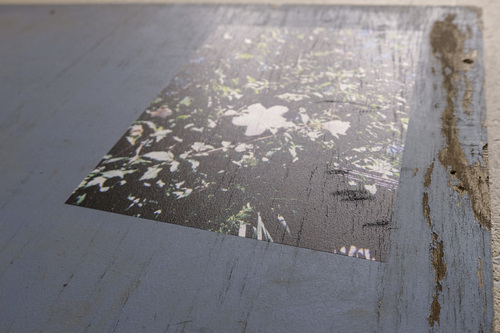

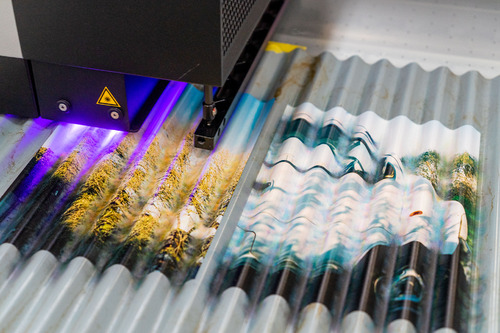

It’s fun to think about printing methods that match the concept of a work or the structure of an exhibition. In addition to printing works on paper, I also use acrylic glass and illuminated boxes or print my photographs onto objects that I found at the beach.

I also create the music playing in the background of my exhibitions. For the exhibition that takes place at two different locations at once, I experimented with streaming audio from one venue at the other.

I think the great strength of the photobook is that it makes it possible to let works leave my hands and have them be seen within situations I can’t reach. It feels strange to imagine that someone who bought my book looks at it in the space of their own homes, that the book blends into their daily life. Another huge advantage of the photobook is that photographs can change depending on the place, the time of day and one’s emotional state.

But I believe both exhibitions and photobooks share the fact that there is depth to them.

Someone told me that the many blank pages in my book “midday ghost” made them feel as if they were suddenly seeing a ghost while walking down a corridor. That made me very happy, as I had been putting a lot of thought into adding depth to the photobook, which many often regard as a “flat” medium.

— Was there a specific reason why you wanted to publish the series in the form of a book?

Hamamoto:

The restrictions that came as part of the corona pandemic were a big factor.

I buy a lot of photobooks myself, and I love photobooks that let me experience views that I have never seen before. I believe photobooks can be tools that allow us to travel across boundaries – not just in a geographical sense, but also boundaries in time and even between life and death.

— I believe you belong to a generation for whom taking photos – via smartphones for example – has been a natural part of their lives since birth. What made you want to begin creating artworks, and use a film camera to create them? Is there a difference to smartphones?

Hamamoto:

You are part of a generation for whom taking photographs – via smartphones, for example – has always been a normal part of life. What made you want to begin shooting photographs as artworks, and why did you choose a film camera to do so? Is there a difference to smartphone photography?

I like the fact that film photographs do not quite capture things exactly as I see them. I bought a film camera very soon after my first encounter with photographs. I used the camera without really knowing how it works, and I enjoyed seeing these completely unpredictable photographs. I still sometimes take photos today with my aperture or shutter speed all messed up. The same is true for broken instax cameras – I get excited about seeing blur that simply could not happen in the real world.

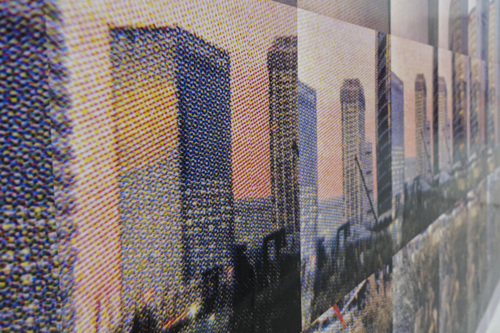

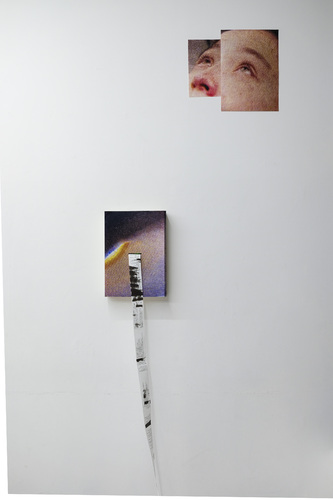

On the other hand, I took all the photographs in my recent series “Vanishing Point” with a smartphone. I put a magnifying lens in front of the smartphone camera and re-shoot already existing photos that way. Searching for the right angle with the magnifying glass feels somewhat similar to taking a photo with a film camera. For “Vanishing Point”, immediately after taking the smartphone photographs, I print them out and paste them on the wall.

I always want to create a three-dimensional space in which to present the photographs, regardless of the tools I use to create them.

— In “midday ghost”, the faults of film photography and broken cameras were actually used as an element to create an atmosphere or a theme. How important are the concepts of “imperfection” or “strangeness” for your work?

Hamamoto:

With the portraits I took with blurry faces, I found the balance between the anonymity due to the blurred face and the individuality that can be read from their hairstyle or their clothes very interesting. I have always strived to create ‘true’ portraits that capture a person without their self-consciousness. I like that my friends seem as if they have no self-consciousness in the photos, because you can’t see their eyes in the blur. They seem like ghosts that have been inadvertently photographed.

Also, I have been interested in the topic of memory for my works since my high-school days. Memory is imperfect and strange; it is not without faults. I think the same can be said about photography. And you can only really capture the past in photographs, too.

The volatility of memory – that it may transform or even disappear at any moment – has certain similarities with badly taken film photographs, I think.

— Why did you choose to blur the faces in the portraits and not, for example, other body parts?

Hamamoto:

One of the themes in “midday ghost” were vague existences without clear definition, and I believe people’s expressions belong to that category as well. People’s faces keep changing constantly; they are one of the midday ghosts for me. Also, when you try to recall a person’s face in your memory, the details of their face become more ambiguous the harder you try to remember them. I hope my portrait photographs captured these imperfections of memory and perception.

— Are there any photobook that left an impression on you?

Hamamoto:

“Because” by Sophie Calle.

To me, photobooks always seemed like a medium that is too preoccupied with visuals and that puts its readers into a passive position, but Sophie Calle manages to involve the audience in an active role with her work.

I think her use of words to evoke images or the act of taking the photographs out of the little pockets creates a great sense of immersion. A variety of places and spaces arise through her book, from the surrounding scenery at the time a photo was taken to the views at her exhibitions. Her book really impressed me, as I’m always thinking about depth in books.

— Do you think there is an artist who has influenced your work?

Hamamoto:

Yes, Hiroshi Yamazaki.

His approach of changing shutter speeds randomly while shooting, and his complex multiple exposure to create something that is ‘different to what the human eye can see’ have influenced me greatly.

He also said that photography is ‘irresponsible and absurdly fun,’ because film photography is an unpredictable act and a lot of things occur that have not been planned. His line that ‘even if a photograph captures nothing, it is still the only photograph like it in the world’ also left a big impression on me.

I had only paid attention to crisp, clear photographs before, but when I then took another look at my photographs after having come across his texts, I discovered new things in photographs that I had simply ignored until then.

Yamazaki also compared multiple exposure photography to the Bill Evan’s album “Conversations with Myself”, in which Evans overdubbed three separate tracks. I thought that interpretation was quite interesting, and since Evans is my favorite pianist I was quite happy he chose that comparison.

— Could you tell us about any new works you’re working on?

Hamamoto:

I am currently working on something like a sequel to “midday ghost.” I traveled throughout Japan by car for the tour exhibition, taking photographs all the time. I want to publish the views and connections that were created as a result of the book in some form.

“Vanishing Point”

This series was photographed with an iPhone and a magnifying glass. It’s my first photographic work that I did not shoot on a film camera.

Here is the statement from an exhibition I held in October this year:

“I often see hypnagogic images.

Like the images you see with closed eyes, shortly before drifting into sleep.

Unlike dreams, there are no emotions, and I can’t control them by will.

I can’t predict my own words and actions at all / so it’s interesting.I wanted to create a series based around these hypnagogic images, and I began interviewing my friends.

But none of my friends had made similar experiences, and so this time I decided to focus my interviews and my series on “dream experiences”:

1: Ask my friends about impressive dream experiences that they have recently made.

2: Ask my friends to find a picture in their camera roll that is the closest to the experience, and have them send the picture to me.

(I believe dreams are based on something we have heard or seen before at some point, hence the camera roll.)

3: I enlarge the images they sent me and print them out

4: Using a magnifying glass and an iPhone, I photograph the images again

5: I enlarge the images again and reposition them.By photographing, analyzing and repositioning the pre-existing images, I tried to visualize a dream, which is collection of jumbled ‘somethings that we have heard or seen before at some point’ that have lost their context.

Photographing the images while using a magnifying glass to peek at their details felt like having stepped inside someone else’s dreams.Also, the process of the images taken from the camera roll crossing from digital to analog, becoming bigger and smaller, feels like the compression and expansion of time within a dream.

VANISHING POINT by Kanade Hamamoto

The series is still work-in-progress.

If you dream or see hypnagogic images, or if you do not dream at all, please let me know your story.”

I want to develop this series in a performance-like or improvisational style in the future, maybe exhibit it in a style similar to the ‘bombing’ from graffiti culture.

Just recently, while I was in Kagawa Prefecture as part of the exhibition tour, I found an old abandoned building. I printed out photographs I had taken in Kawaga in a convenience store and held an impromptu exhibition in the abandoned building.

“autonoetic”

This exhibition is currently taking place in Tokyo. Here is the statement:

“autonoetic

(the ability to place oneself mentally in past and future situations, including possible forks, and examine the self and one’s thoughts)A part of a house, weathered by the years; a piece of wood formed into a round shape in the rough waters of the ocean. Unique objects and sights like these reveal to us a faint idea of their former owner or let us imagine the things that they have witnessed throughout their life.

‘What have these objects seen and experienced?,’ we wonder.

The interweaving of time contained in objects and photographs – the long-term changes witnessed by objects, the single instances captured within photographs.In this series, the carrier medium of my prints were metal sheets and plywood washed up at the beach, or old wood from demolished houses.

What they all have in common is that they used to belong to someone else, someplace else.”This series is also still work-in-progress. In the future, I want to use an entire old house for this exhibition:

Stay in the old house and take photographs -> demolish the house and print all photographs shot there onto the rubble -> reassemble the printed-on building materials, and so on…”

I am also working on other, yet untitled series.

Thematically, I am very interested in coexistence with nature and disintegration, and I’d like to exhibit my works outdoors or in abandoned buildings.

Whether through books or exhibitions, I want to continue creating spaces that make use of all human sense to present my works in the future.

*Kanade Hamamoto “autonoetic”

November 2, 2020 – February 19, 2021

Location: Terrace Square 1F, Kanda Nishikicho, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo

Open 8:00 – 20:00 (closed on weekends and holidays)

Entry free

Kanade Hamamoto

Born in Yokohama in 2000, raised in Fukuoka Prefecture. Based in Tokyo and Kamakura, Hamamoto creates photographic artworks, installations and exhibitions. In 2018, she held her first exhibition “mi-kansei” in Kamakura. In 2019, she held the solo exhibition “reminiscence bump” in Shibuya, followed by “midday ghost” in 2020, held at Omotesando Rocket and Studio Staff Only galleries simultaneously. In 2020, hito press published her first photobook “midday ghost.”